Telescopes are very complex facilities, with lots of different instruments and systems carefully calibrated to harmoniously work together. To achieve that, design and development activities must proceed in parallel, and there must be continuous adjustments between the different systems and subsystems without losing sight of the scientific objectives. It's like a dance, and choreographing it is the task of systems engineering.

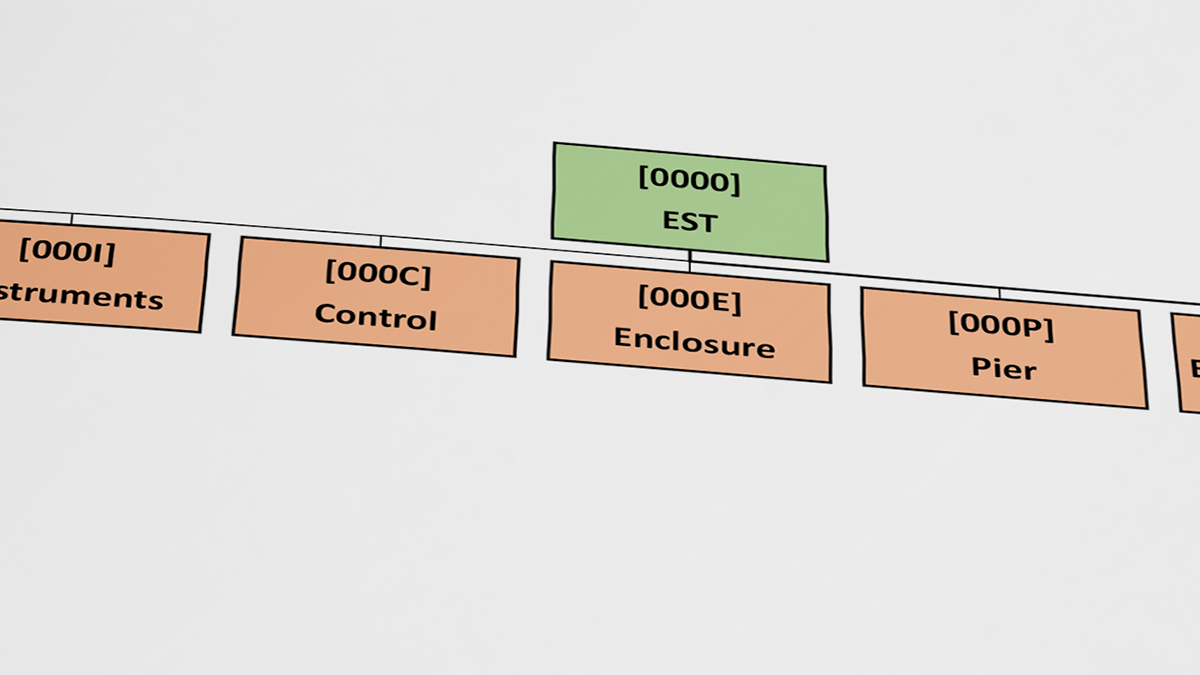

Part of the EST product tree. The product tree is an essential tool for systems engineering. It lays out the different elements of the telescope structure (optics, instrumentations, control, enclosure, pier...) and its subcategories, also showing the relations between them.

Part of the EST product tree. The product tree is an essential tool for systems engineering. It lays out the different elements of the telescope structure (optics, instrumentations, control, enclosure, pier...) and its subcategories, also showing the relations between them.

Broadly defined, systems engineering is an interdisciplinary field that focuses on how to design, integrate and manage complex systems. It’s a field of pivotal importance in many industries, from transportation to software. In the case of the European Solar Telescope, the role of the systems engineer is to make sure that the telescope is aligned with the scientific vision while doable in terms of time, money and overall system integration.

This means that, to some extent, the systems engineer acts as a ‘mediator’ between the scientists' wishes and the engineers’ practical, down-to-earth approach. That is not as straightforward as it might seem, because in EST —like in any other large astronomical facility— instruments are intended to do something new, or to perform better than previously achieved. This adds a layer of complexity that renders particularly challenging the task of balancing vision —the scientific goals that researchers want to achieve— and feasibility —assessing the best that cutting-edge technology can offer for each subsystem without compromising the others (or exceeding time or money constraints).

Managing this delicate equilibrium is the daily job of EST Systems Engineer Miguel Núñez, choreographer-in-chief of the European Solar Telescope: "My role is to have a clear picture of the scientific goals that must be met by both the telescope as a whole and each of its parts, as well as to understand the relationships between the different systems and subsystems", explains Núñez.

Trees, budgets, and racing cars with proper wheels

In order to do so, systems engineers elaborate the product tree, a chart displaying the different structural elements of the telescope plus the relationships among them. This comes in handy when preparing the "error budget", an accounting system that keeps track of the margin of error allowed for each scientific case (scientific cases are detailed in the Science Requirement Document or SRD, the bible of the telescope).

"For instance, scientists could tell us that the image quality can only have a certain margin of error as far as the wavefront is concerned. That margin, although small, will be different from zero [it is not possible to create systems without any kind of error]. What we do is to divide the margin among the different systems and subsystems, so that we know what margin of error we can afford in each optical or mechanical component", outlines Núñez. “So, if an engineer tells me «look, it's not possible to achieve this», I know what scientific case is driving the requirement, and whether there are any other elements that can compensate for that element", he continues.

"Since there are specialists for the different systems, one may wonder what the point of having a systems engineer is if everything has already been taken care of”, reckons Núñez. “Well, the point is to be sure that, when everything is put together, we have the telescope we were aiming for and that we don’t end up with a racing car with a sport body but the wheels of a tractor, no matter how well designed they are. So the point is to make sure that the final telescope is coherent with our vision”, concludes Núñez.